AI can now create art, make music and generate extremely life-like videos, but one of the world’s best known music producers believes that it won’t necessarily replace artists.

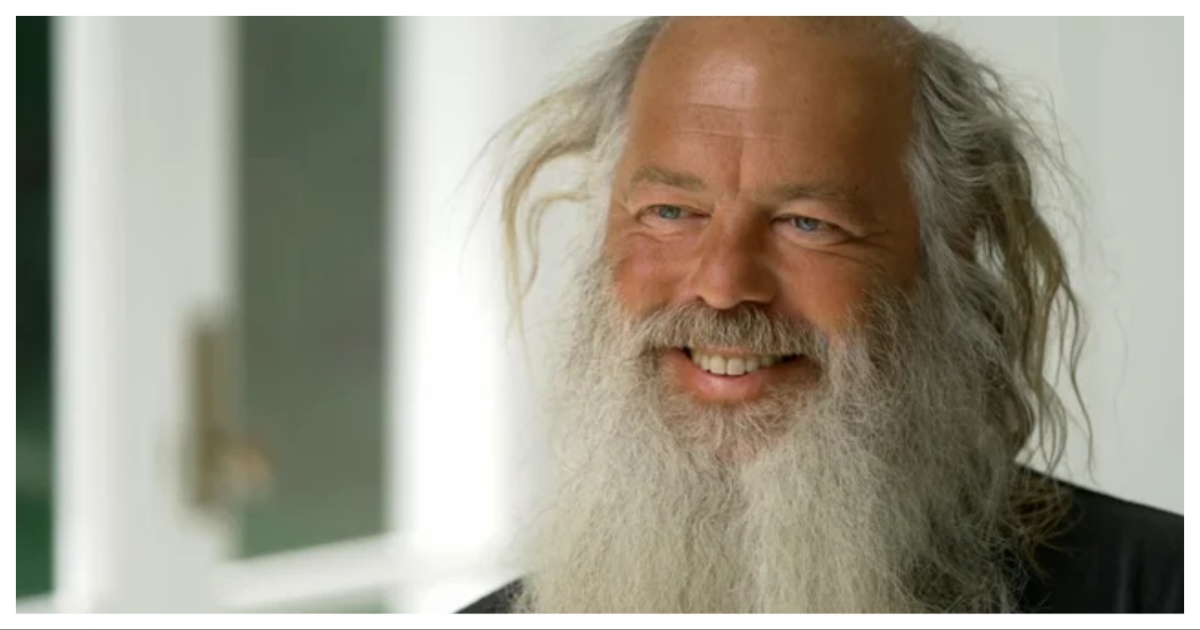

Legendary music producer Rick Rubin, who has shaped iconic albums for a vast spectrum of artists from Johnny Cash and the Red Hot Chili Peppers to Jay-Z and Adele, has dismantled the fear that AI is coming for the artist’s job. Instead, he reframes it as a powerful new instrument in the creator’s arsenal, arguing that technology can’t replicate the one thing that defines true art: a point of view.

For Rubin, the distinction is clear. The magic of creation doesn’t lie in the tools themselves, but in the unique perspective of the individual using them. “I think there’s a misconception that the computer now does the work, but really the computer is another tool,” he explains. “It’s like a guitar or a sampler; it’s another tool in the artist’s arsenal. The reason we go to the artists we go to, or the writers we go to, or the filmmakers we go to, is for their point of view.”

This is the fundamental element that Rubin believes AI currently lacks. “The AI doesn’t have a point of view. Its point of view is what you tell it,” he states. To illustrate, he points to the interpretive nature of art: “You can have a great script for a film, give it to five great directors, and you’ll get five very different movies. It’s true with everything. If you give the same song to different artists, they interpret it differently.”

So what role does AI play? Rubin sees it as a remarkable facilitator for the artist’s vision, a way to accelerate the exploration of ideas. “AI gives you the ability to take your ideas, feed it into this machine, and then get back different iterations that you would normally do, but it would just take you much longer. It’s more of a modeling process,” he says. “You’re not just asking it to make art. You’re asking it to bring your dreams to life, in the same way that you would in a woodshop.”

Ultimately, the agency and the soul of the work remain firmly with the human creator. “It’s just another tool for you, as the artist, to make the thing that you want to make,” Rubin concludes. “If you think it’s doing it, it’s only doing what you’re telling it to do. All it knows is what other people have told it to do. I don’t know that it has any of its own thoughts yet, and I don’t know if it’s possible.”

Rubin’s analysis provides a crucial dose of reality in the often-hyperbolic discourse surrounding AI. His argument champions the irreplaceable value of human experience, intention, taste, and emotion—the very ingredients that forge an artistic point of view. An AI can be prompted to write a song in the style of Bob Dylan, but it hasn’t lived the life, felt the heartbreak, or witnessed the societal shifts that informed Dylan’s lyrics. It is executing a complex mimicry of patterns, not expressing a singular, lived truth.

This perspective is already being borne out in how creative trailblazers are engaging with AI. For instance, look at the music artist Grimes, who launched her Elf.Tech platform to allow others to use an AI version of her voice in their own creations, offering a 50/50 royalty split on successful tracks. She isn’t being replaced; she is extending her artistic identity and collaborating at scale, with her point of view as the foundational element. A more historical example is the release of The Beatles’ “final” song, “Now and Then,” in 2023. Director Peter Jackson’s production team used a bespoke AI to “demix” an old demo, cleanly isolating John Lennon’s vocals from a piano. The technology was a bridge across time, a restorative tool that allowed the surviving band members to fulfill an artistic vision that was previously impossible.

What Rubin’s insight and these real-world examples signal is a future defined not by replacement, but by partnership. The artists who will thrive are those who, as Rubin suggests, can master this new tool and direct its immense power with a clear and compelling vision. The fear of a “ghost in the machine” overlooks the fact that, for now, the ghost is merely a sophisticated echo of the artist at the controls. The tools will undoubtedly become more advanced, but the fundamental human craving for connection through an authentic, singular perspective will, as it always has, remain the soul of art.