There has been no shortage of accusations around how Amazon has been flouting Indian laws with impunity, but a new report shows how widespread — and blatant — the violations might have been.

Amazon copied other products and rigged its search results to favour them, a bombshell Reuters report has revealed. Reuters claims to have accessed thousands of pages of internal Amazon documents, including emails, strategy papers and business plans, which show how the company ran a systematic campaign of creating knockoffs and manipulating search results to boost its own product lines in India. In the past, Amazon has repeatedly denied using the data collected from its platform to create and sell its own products.

The new Reuters report claims that Amazon’s private brands team in India secretly exploited internal data from Amazon.in to copy products sold by other companies, and then put its own products at the top of its search results. A strategy report from 2016 showed how Amazon put its own products “in the first 2 or three … search results” when customers were shopping on Amazon.in. In effect, after letting other brands sell on its platform, Amazon copied their products, and then pushed its own products towards the top of search results, effectively stealing their business.

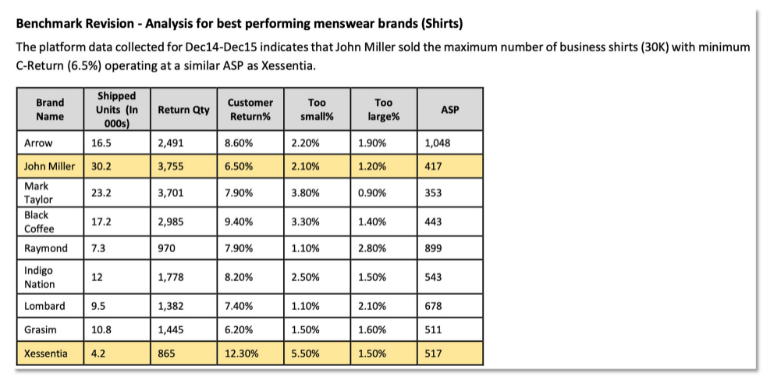

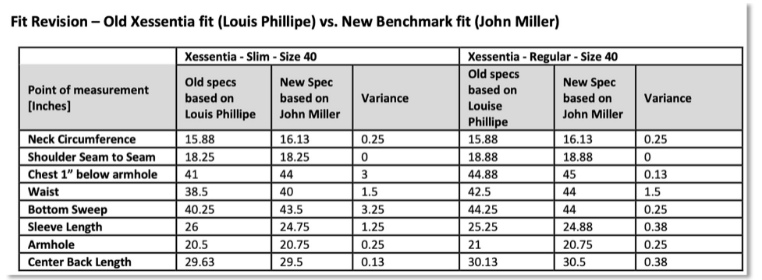

In one case, Amazon allegedly copied the exact dimensions of shirts sold by Aditya Birla-owned Louis Philippe for its own Xessentia line of shirts. But Amazon discovered that that return rates of its Xessentia shirts was higher than those of competing products. Amazon then studied the return rates across brands, and noticed that the return rates of Kishore Biyani-owned John Miller were much lower in comparison. Amazon then went ahead and copied the exact dimensions of John Miller shirts for its own Xessentia line, inch by inch.

Most worryingly, it would appear that these initiatives weren’t the work of a truant team or a handful of employees — the report alleges that two senior Amazon executives executives reviewed the India strategy, including senior vice presidents Diego Piacentini, who has since left the company, and Russell Grandinetti, who currently runs Amazon’s international consumer business.

The allegations, if true, are exceedingly serious. For starters, India’s FDI rules don’t allow e-commerce companies to sell their own products on the platforms they run, but Amazon has been subverting this rule through third-party entities like Cloudtail. More brazenly, Amazon also used the data collected from its own platform to copy products which it saw were doing well, and then pushed its own products at the top of search results. This, in effect, cannibalized the business of local Indian brands who were selling on Amazon.

Kishore Biyani’s Future Group said that it was “shocked and surprised” to learn that Amazon was using Indian brands to build its own. “They are in a powerful position of being both an online marketplace operator and a seller and collector of data,” the spokesperson said in a statement to Reuters. “This is leading to misuse of consumer and seller data giving them the power to kill Indian entrepreneurs and their brands.”

Amazon, for its part, has remained non-committal about the charges. “As Reuters hasn’t shared the documents or their provenance with us, we are unable to confirm the veracity or otherwise of the information and claims as stated. We believe these claims are factually incorrect and unsubstantiated,” Amazon said.

But this is hardly the first time that Amazon’s business practices have come into question in India. Earlier this year, another bombshell Reuters report had accessed communication between Amazon and US officials to suggest that the company had deliberately skirted FDI laws in India. India’s FDI rules don’t allow e-commerce companies to also sell products on the platforms they operate, but Amazon, through a group of companies it had influence over, circumvented these rules and made large sums of money. In June, an investigation by the Guardian found that Amazon had received a tax demand of Rs. 54 crore from Indian tax authorities for not adequately paying taxes in the country. Amazon is also being investigated Competition Commission of India (CCI), for alleged anti-competitive practices, predatory pricing and preferential treatment of sellers. Just last month, another report had alleged that Amazon had bribed government officials, and had sent its senior counsel on leave pending an enquiry.

It’s astonishing that Amazon appears to be able to continue to do business in India in spite of such grave accusations, but Amazon — and Flipkart — have seemingly become too big to fail. Thousands of crores of sales take place on these platforms each month, and through low prices and fast services, the two services have turned into a virtual duopoly. But India has suffered through such tactics in the past — East India’s Company’s traders too had reached India several centuries ago to do business, gradually displaced local traders, and eventually took over the entire country. India would do well to quickly learn from its history before it’s too late — the modern incarnations already appear to have begun showing a brazen disregard for the country’s laws.